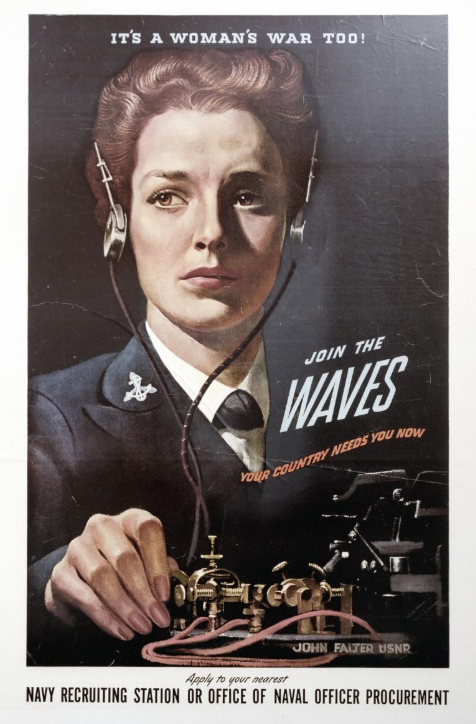

Women who served in the Navy WAVES stationed in Dayton played a pivotal but lesser-known role in intelligence operations that turned the tide of World War II.

Story provided by Anna Helmig-Sampson, Database and Records Manager, National Aviation Heritage Area.

The Navy WAVES’ Top-Secret Mission in Dayton

While Dayton is often celebrated for its aviation legacy, its role in World War II extended far beyond aircraft production and research. One of the city’s most critical yet lesser-known wartime efforts took place at the U.S. Naval Computing Laboratory, where hundreds of WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) worked in secrecy to assemble codebreaking machines that helped defeat the Axis powers. Their efforts in Dayton were a pivotal part of the intelligence operations that turned the tide of the war, further cementing the city’s place in military history.

The WAVES program was established in 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Navy Women’s Reserve Act into law. The WAVES’ primary role was to fill the United States Navy’s onshore, home-front positions that were left vacant by sailors fighting overseas. Most WAVES were assigned to positions in naval aviation units, repairing aircraft, working in domestic air traffic control, and training sailors on celestial navigation. Others worked in a variety of naval assignments including clerical, weather forecasting, engineering, pharmaceutical, and medical positions. However, approximately 600 WAVES were assigned to Dayton, Ohio, to begin work on a very different sort of mission that they were told nothing about.

The WAVES “Land” in Dayton

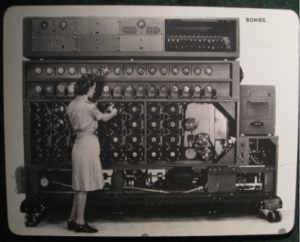

The first WAVES arrived in Dayton in April 1943, reporting to the U.S. Naval Computing Laboratory, located in Building 26 of the National Cash Register Company (NCR). The U.S. Navy charged NCR, under the direction of Joseph Desch, with developing code-breaking machines, called “bombes,” that could decode the German Enigma device that provided communications with U-Boats. This work was meant to expand on the accomplishments of Alan Turing, who had successfully created a three-rotor bombe to counter earlier-versions of the Enigma at the United Kingdom’s Code and Cypher School at the beginning of the war.

Intense Secrecy Required

Because this work was secretive, the WAVES working on the project were not told specifics about what they were making, nor were they allowed to discuss any aspect of their work with one another, let alone their friends and families on the outside. In fact, it wasn’t until decades later, when the project was declassified, that the WAVES would learn just how vitally important their work was to the war effort.

Betty Robarts, a Dayton-based Navy WAVE, found out in 1995 during a WAVES reunion the true impact of her work in Building 26. Betty was so overcome that she “cried for months,” explaining that she and her fellow former WAVEs were “shocked” to learn the true nature of their work. This intense secrecy, however, did not stop the WAVES from committing themselves to their job wholeheartedly.

Intensive and Demanding Work

Working around-the-clock in three shifts, six days a week, the WAVES assembled the bombe machine’s electromechanical components, following highly specific technical instructions. After the machines were made, they tested and ensured their functionalist by using controlled ciphers, performing maintenance, and troubleshooting any problems. The work was difficult in that it was extremely meticulous and complex, requiring long hours of intense focus and strict adherence to technical diagrams to correctly place thousands of tiny pieces.

Not All Work – Life at Sugar Camp

Outside of their work in Building 26, the WAVES lived, rested, and played at Sugar Camp, a former NCR sales training camp that was located a mile from the NCR complex. The camp was equipped with sixty wood cabins equipped with beds, desks, closets, and a shared bathroom. Each cabin was meant to sleep four people, measuring fourteen by thirty-five feet. However, during peak seasons of the project, up to twelve women would share a single cabin, sleeping in shifts while their roommates worked and trading places throughout the day. Despite cramped conditions, difficult work, and the general anxiety surrounding the war, the WAVES did their best to enjoy the recreational activities that Sugar Camp and Dayton had to offer.

The camp itself had a dining hall, pool, baseball diamond, basketball court, recreational building, and beautiful wooded grounds for walks. Much of the women’s free time was spent writing and reading letters to and from loved ones, including significant others fighting overseas. Oftentimes, groups of WAVES would venture outside of camp to enjoy the city of Dayton and visit theatres, shops, restaurants, bars, and even the skating rink.

Daytonians Welcome WAVES with Open Arms

The people of Dayton welcomed the WAVES with open arms, offering rides to the NCR complex when they saw the women marching from Sugar Camp to their work in the rain.

In an interview conducted by the former Montgomery County Historical Society (now Dayton History) in 2001, a former WAVE, Sue Unger Eskey, recalls: “…all the people [of Dayton] were always good to us…. I say, [Dayton] sort of became our hometown, too. Because this is the way we were treated at home.”

Another woman, Dorothy Braswell, had similar recollections of being welcomed by Daytonians during her time in the WAVES. She even had the chance to meet one of the city’s most-famous celebrities during her time in the city, recalling:

“…I was at some celebration up at the Carillon and I had the very special honor to meet Orville Wright. I was so thrilled to shake his hand and tell him I was from North Carolina. He was such a sweet and shy little man and I didn’t wash my hand for weeks.”

Dayton’s Hospitality Turns to Romance for Some WAVES

Many of the women even found love in Dayton, especially in the large number of military men stationed at Wright Field. Twenty-four WAVES married during their time in Dayton, including Peggy Cox and Doug Whittaker, a Wright Field pilot, who met at a party held at Sugar Camp, and Vivian Kurtz and Paul Kintner, of the Army Signal Corps, who met at a Dayton YWCA dance.

A Successful Secret Mission Completed

In the three years the WAVES spent stationed in Dayton, the U.S. Naval Computing Laboratory was successful in their mission to construct improved codebreaking devices. Desch’s bombe design proved to be six-times faster at decrypting the Enigma codes than the earlier British version. Furthermore, the NCR bombes were able to successfully work against the German’s improved four-rotor Enigma machine. By the end of the war, the WAVES had assembled one hundred and twenty bombes in Building 26. The machines were massive, each weighing over two tons and measuring over ten feet long and seven feet tall, full of thousands of interworking pieces, including drums, wire brushes, electrical circuits, rotors, and resisters. Each one of these Dayton-assembled machines played a critical role in the Allies’ war efforts, deciphering critical German military communications. This intelligence provided the Allies with a massive strategic advantage, allowing them to anticipate enemy movements, protect their own envoys, and launch successful counteroffensives- likely saving thousands of lives. The WAVES’ contribution to this effort was indispensable, as their meticulous assembly and maintenance of the bombes ensured their reliable operation in the field.

A Lasting Legacy

Beyond their wartime contributions, the WAVES stationed in Dayton left a lasting impact on military intelligence technology and, in an indirect way, the aerospace industry. Their work with the Naval Computing Laboratory at NCR was an early example of women playing a critical role in technological and engineering advancements within the U.S. military. Many WAVES who gained technical expertise during their service went on to pursue careers in engineering, aviation, and computing, helping to shape the critical postwar aerospace industry. Furthermore, their presence at a pivotal moment in Dayton’s history strengthened the city’s legacy as a hub for world-changing innovation, alongside the work of the Wright Brothers and countless other inventive Daytonians.

Explore More About the WAVES in Dayton

If you enjoyed learning about the WAVES’ cryptological work in Dayton, be sure to pay a visit to Carillon Historical Park, where you can check out a surviving Sugar Camp cabin outfitted as it would have been during World War II. To learn more about Montgomery County’s World War II Heritage City designation, click here: https://www.nps.gov/places/montgomery-ohio.htm.

A Very Special Event with Sir Dermot Turing – May 8, 2025

On May 8, 2025, Sir Dermot Turing, author and nephew of famed cryptologist, Alan Turing, will visit Dayton for a VE Day event. Turing will speak on his uncle’s contribution to the war effort and general cryptology topics at two events at the International Peace Museum and Carillon Historical Park.

Sources:

Keeping the Secret: The WAVES & NCR Dayton, OH 1932-1946 by Curt Dalton

Sue Unger Eskey, interview by Claudia Watson, Montgomery County Historical Society, during the WAVES reunion, October 20, 2001, https://daytoncodebreakers.org/personnel/interviews/sue/.

Navy WAVES Building Decryption Bombes in Dayton, Ohio by Sarah Nestor Lane for the National Park Service World War II Heritage City Program, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/-h-our-history-lesson-navy-waves-building-decryption-bombes-in-dayton-ohio.htm

Barrie Barber, “Dayton’s WWII Role No Longer Secret,” Dayton Daily News, (last accessed 11 March 2025), https://www.daytondailynews.com/news/local-military/dayton-wwii-role-longer-secret/4pXg9x4wEWAmYZaFD5f8ZO/.

Photo Credits:

Image 2: A US Navy WAVE sets the Bombe Rotors (Photo Courtesy of brewbooks CC BY-SA 2.0, flickr) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Navy_Cryptanalytic_Bombe.jpg

Image 3: A WAVE in her cabin at Sugar Camp, May 9, 1943. From the NCR Archive at Dayton History.

Image 4: Two WAVES walking through Sugar Camp, May 26, 1943. From the NCR Archive at Dayton History.

Image 5: One of the Sugar Camp cabins today, preserved at Carillon Historical Park.