A TRIBUTE TO LTC CHARITY ADAMS EARLEY

ON THE RE-COMMISSIONING OF THE DAYTON VA WOMEN’S CLINIC IN HER HONOR, June 12, 2024

by Frances E. McGee-Cromartie, family friend and mentee; America 250-Ohio Under-Told Stories Co-Chair

About LTC Charity Adams Earley

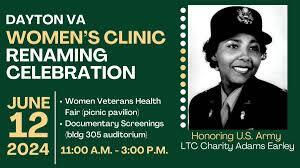

Official U.S. Army portrait of Charity Adams Earley, the first African-American woman to be an officer in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

Charity Adams Earley led the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion who is credited with untangling two years of postal backlog in Europe that was piling up in six airplane hangers unable to be delivered until the “six triple eight” took charge. A new Netflix film depicts their story. (Trailer)

Maj. Charity E. Adams and Capt. Abbie N. Campbell inspect members of the 6888th Central Postal Delivery Battallion of the Women’s Army Corps. Feb 15, 1945

Ohio Connections

Charity Edna Adams was born in Kittrell, North Carolina and grew up in Columbia, South Carolina. When it was time to seek higher education, she came to Ohio to attend Wilberforce University in 1938, where she majored in math and physics and joined the Beta chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. She would later attend The Ohio State University where she would receive her Masters in psychology in 1946.

After the war, she married Dr. Stanley A. Earley, Jr., and after Dr. Earley completed his medical training in Switzerland in 1952, they returned to the U.S. and settled in Dayton, Ohio where she would live the rest of her life.

In Dayton, she was an active and engaged citizen volunteering and provided leadership on numerous civic and community organizations. Recently, the Dayton VA Women’s Clinic was renamed in her honor.

Honored in Dayton with re-commissioning of the Dayton Women’s VA Clinic in her name.

The following are remarks made by Frances McGee-Cromartie on the occasion of the dedication of the Dayton Women’s VA Clinic re-commissioned in honor of LTC Charity Adams Earley on June 12, 2024.

“Members of the military, family, friends and guests, I am Frances McGee-Cromartie, and I am honored to be given a few minutes to talk about my friend and mentor, Mrs. Charity Edna (Adams) Earley.

When I first joined the Daughters of the American Revolution more than 6 years ago, one of the first projects that I wanted to do was to honor Mrs. Earley’s contributions to the area, the state and to our country; however, due to roadblocks that had to be overcome, the program was not able to be brought to fruition. So when I heard of this program, I made sure to mention my connection to this unique woman warrior and veteran to ensure that those speaking of her remarkable life would give her the full measure of honor she is due.

You see it is my belief that although her family is quite proud of the honors that are being bestowed upon her now, it was an injustice to our American values and American history to fail to extol this woman’s legacy during her lifetime. By failing to recount the importance of this African American woman’s leadership and tenacity during World War II, many in this community missed an opportunity to see American Greatness in action. So, to those who pushed this honor through the endless miles of red tape and hesitation, I say thank you!

Although I had known Mrs. Earley all of my life, the Earleys moved to Dayton before I was born and became friends of my parents who had moved to Dayton several years prior, I did not get to know her as a friend until the last 20 years of her life. Due to the de facto laws of segregation and gender roles that permeated Dayton and the United States, it took the white community longer to acknowledge my mentor.

In the 1950’s women had set roles as wives and mothers. Upon marriage, these roles were further limited to certain proscribed volunteer roles that would serve to help their husbands move ahead professionally. Under these conditions, Mrs. Earley and my mother, the late Mrs. Betty McGee, became friends.

My father, the late James H. McGee and Dr. Earley bonded professionally and through their involvement in local civil rights activities. Later both men were initiated into Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity or the Boule, the oldest African American Fraternity in the United States and so the families continued their ties of friendship and service.

It wasn’t until the year 1981 when I moved back to Dayton to marry and begin my legal career, that I learned the story of Charity Adams.

Forming a friendship

“My friendship began when I was selected to be a member of the nation’s first Black Leadership Development Class. The program resulted from a meeting convened by local businessmen who wished to create a strategic plan for the community leading into the 21st Century leaders. However, the community’s response to the eight proposals set forth by these business leaders was lukewarm at best; they were asked to re-convene and return after addressing a ninth issue—their failure to include the African American community in their vision.

The excuse for this omission was dissatisfaction with the existing pool of African American leaders. This excuse was rebutted by the African American leaders who argued that the small class of leaders that these alleged visionaries turned to were not their only choice. The groups compromised by creating a leadership program that would produce a cadre of young leaders prepared to sit on the boards and committees as area visionaries. My father, as former Mayor of Dayton, was this program’s honorary Chair, while Mrs. Earley and Mr. John Moore were named the actual chairs.

Under the leadership of these two community advocates, a tough yet stellar program was created and implemented. From September 1982 to April 1983, we met every other Saturday morning to learn the mechanics of leadership, boardsmanship, power, and politics along with area history. At the end of the first year, and impressed by the influx of new leaders, the directors of Leadership Dayton revamped their program to mirror ours by including an African American history component and by incorporating our speakers into their programs.”

Getting to know Mrs. Earley personally

“Soon after, I became a part of the Black Leadership Development Program’s Steering Committee and got to know more about Mrs. Earley. Mrs. Earley was tough and demanding. Each member was evaluated and received feedback on their attentiveness, preparedness, timeliness and most of all it was drilled into us to remember always why we were asked to serve.

In addition, we learned to never back down when the situation demanded courage of conviction. I recall how Mrs. Earley used these tenets when she went toe-to-toe with a community leader who greeted her condescension and arrogance. With every ounce of calm dignity, she held her ground with a smile and her no-nonsense persona. Leaving the meeting, I recalled a joke that my law school professor once told. He said that he observed a legal argument between two worthy opponents that ended with one opponent not knowing that he had been effectively bested until he tried give his opponent a nod. Only then did he realize that his head was severed from his body.

Sharing Memories

“I served on the Steering Committee approximately 10 years and it was during this time that I learned Mrs. Earley was going write a memoir and we had several conversations about her memories.

The first that I remember came when I asked her how she was going to record her thoughts. It was the late eighties and personal computers were just coming into vogue. I remember asking, “Are you going to use a computer or typewriter?” “Neither” she replied with a twinkle in her eyes. “I’m going to use a pencil and yellow lined paper.”

In later conversations, Mrs. Earley mentioned to me incidents that she wanted to put into her book entitled One Woman’s Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC. Through these anecdotes I learned how the metal that this woman received at birth was forged into the best steel. Here are the words I remember:

“I became the first Black female Commissioned Officer only because we went by alphabetical order,” she said modestly with another twinkle in her eye. I took this to mean that she and her other officers in training were all well-prepared, but she was happy to have the last name of Adams and to be named first.

Mrs. Earley was unafraid to remember and bear witness to positive and the negative experiences she had in the service and for that I was grateful. The members of the Six Triple Eight Unit, that she led, were assigned an important, yet impossible task—to remove a two-year mail delivery backlog immediately. Letters from home improved military morale. One of Mrs. Earley’s superior officers believed that this Negro unit did not possess the intelligence or stamina to take on this task and threatened to replace her unit with a white one.

“Over my dead body, sir,” was the crisp reply that could have resulted in a court martial rather than the successfully recorded result. By dividing her unit into three eight-hour shifts that worked around the clock, the group was able to beat the deadline set.

However, for me, the most painful reminder she related occurred after completing their first assignment. The unit was ordered to repeat their triumphant mission in another venue. Mrs. Earley’s subordinates were given limited ability to fraternize with other soldiers, especially foreign soldiers. The superiors of those servicemen asked and received from her permission to meet. She was puzzled to hear her charges would return an hour before curfew.

Upon inquiring about this statement, Mrs. Early was told that the American GI’s stated that if the women were brought back any later, they would transform into monkeys and the women’s tails could be seen. I believe that this anecdote was related to remind me that while some improvements in the human condition had been made in the 40 years since WW II had occurred, I must always remember that as a community leaders, it was my duty to speak up and be a role model for change.

Final thoughts

“In conclusion, I want to state that it is possible for someone in this audience to have looked at the beautiful military photo of young Charity Edna Adams and wondered why she, of all people, would receive such an honor. In response, I would note that you, dear skeptic, are the one who should be humbled to know that every time you cross the threshold of this building, you have the opportunity to absorb a tiny bit of the courage, valor and integrity of this American warrior. I would ask you to remember with pride the life and service of an American ‘shero.’ Let us never forget the contributions to American history of Charity Adams Earley and the women of the Six Triple Eight.”

Frances McGree-Cromartie is a community volunteer, former judge, member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and co-chair of the America 250-Ohio Under-Told Stories Committee.